What are natural capital and ecosystems services?

The ever-increasing range of environmental terms can be hard to keep up with. Here we will demystify the difference between ‘natural capital’ and ‘ecosystem services’ and consider how bringing a conceptual landscape overview to these ideas can strengthen them.

Defining the terms

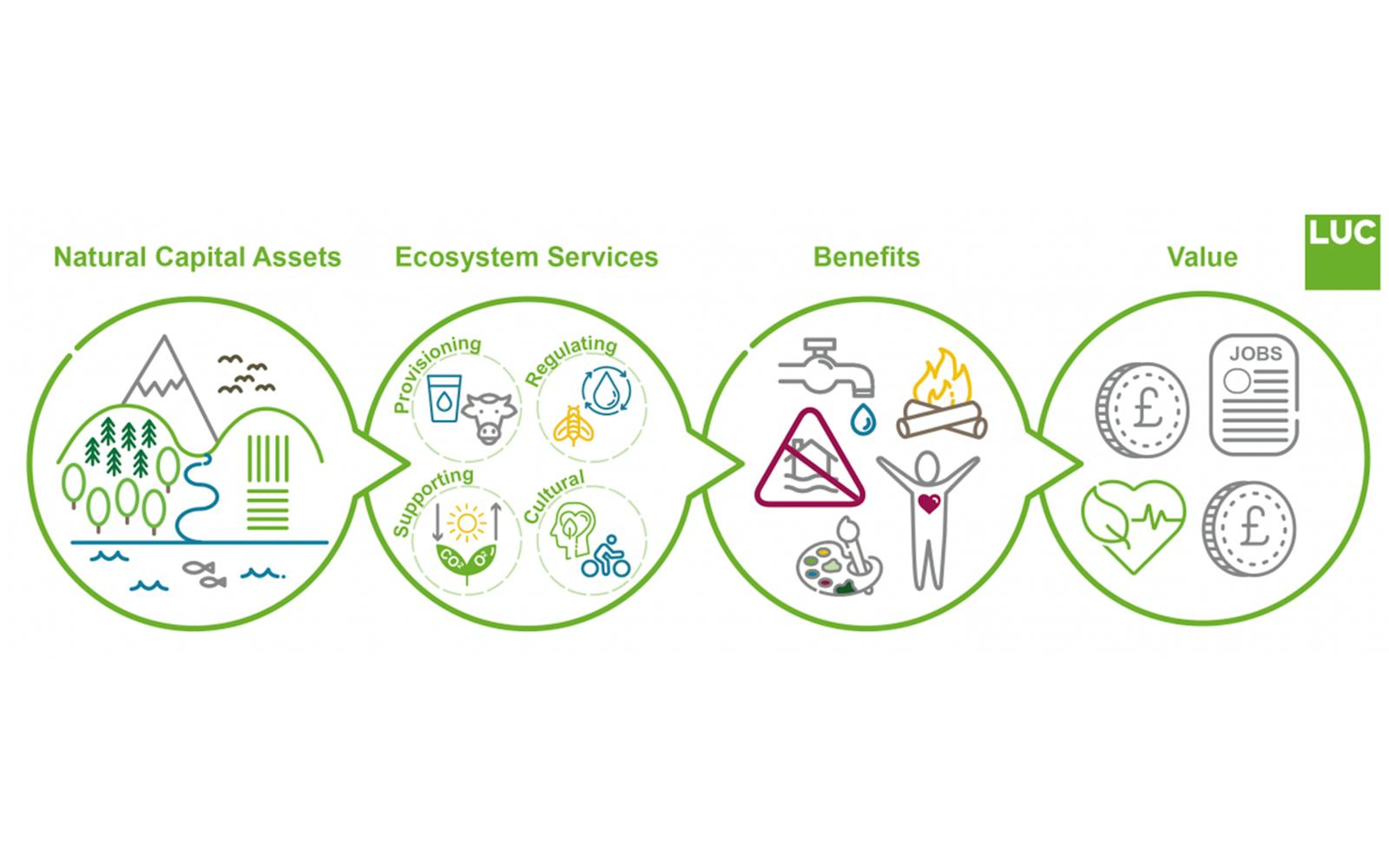

Natural capital describes the natural assets in the world around us, such as plants, rivers, soil and animals.

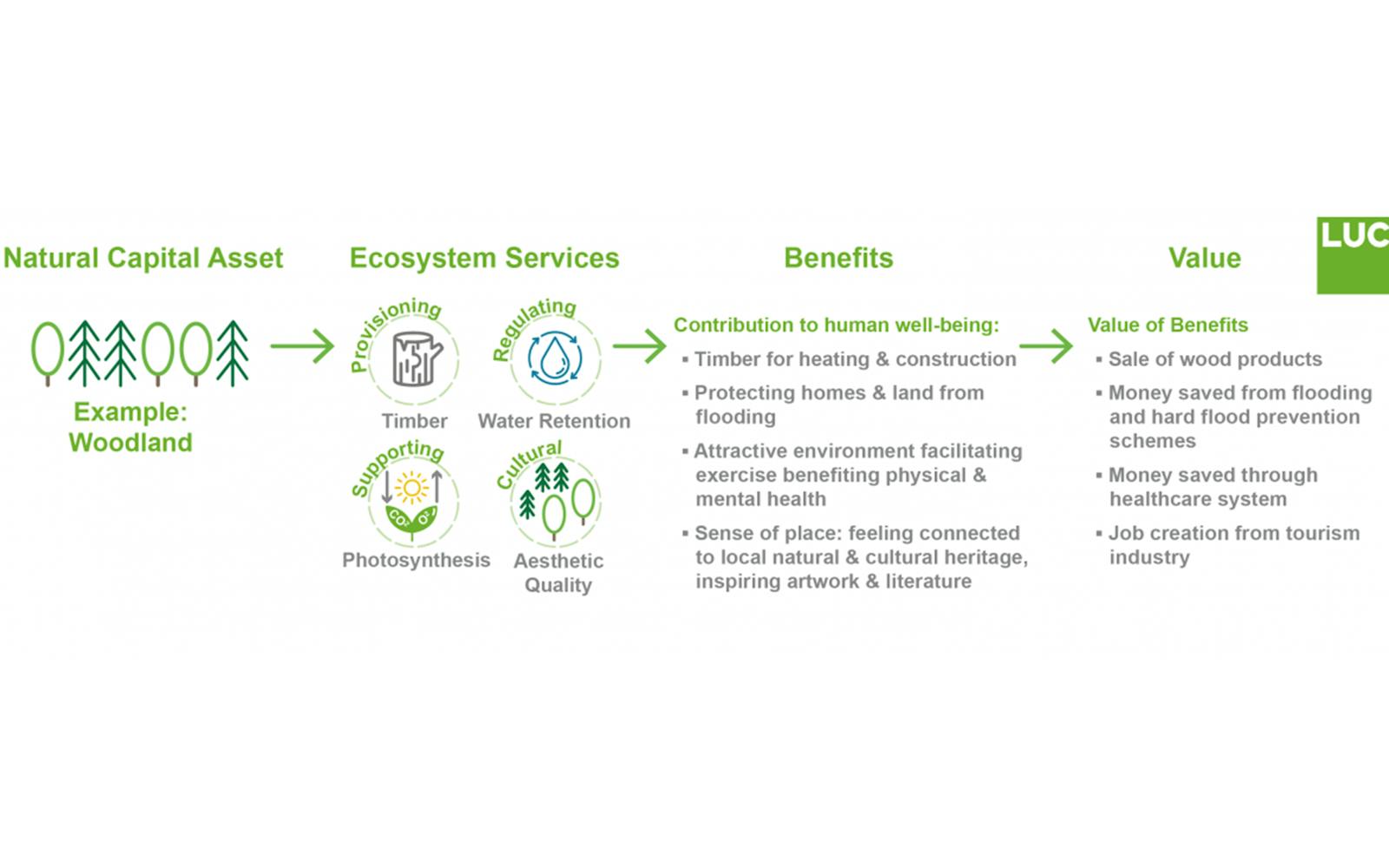

Ecosystem services describe the flow of benefits which we gain from this natural capital. For example, a woodland is a natural capital asset, from which the ecosystem services of supplying wood fuel, reducing water run-off and providing a peaceful retreat can be gained.

Ecosystem services are divided into provisioning services, regulating services, supporting services and cultural services.

- Provisioning services provide products such as food or water.

- Regulating services regulate a natural process to our advantage, such as reducing flooding or air quality.

- Supporting services provide services to help other ecosystem services function such as photosynthesis and soil formation.

- Cultural services provide non-material benefits essential to our health and wellbeing such as sense of place, recreation and aesthetic quality.

Ecosystem services can both provide direct, clearly distinguishable benefits such as such as employment in agriculture or flood reduction but also indirect, less tangible benefits. For example natural capital contributes collectively to sense of place, which in turn supports people’s wellbeing, recreation and the tourist industry.

Valuing natural capital and ecosystem services

Natural capital and ecosystem service assessments are used to measure the extent and quality of natural capital and the degree of benefits we gain from it. So, these methods can be used to quantify and compare the value of different components of the natural world.

Skepticism has been expressed about this commodification of natural resources and objections raised to monetising the natural environment. However, these approaches can help to highlight the extent to which we are dependent on our natural resources and illustrate how investing in them now will ultimately save money.

For example, by illustrating the time and money saved by water companies regulating water quality through land management in upland catchments. It is easy to make the argument for the environment to environmentalists, but natural capital and ecosystem services allow us to make that argument compellingly to economists, developers and politicians. In addition to this it allows clearer evaluation of the financial costs and benefits of different policies, decisions or actions.

Challenges of valuing nature

Although these approaches have become widely accepted and applied, valuing nature is challenging, and some aspects are easier to achieve than others. For example, we can calculate how much wood a plantation produces with relative ease, but calculating the value of cultural services, such as the benefits derived from those strolling through woodland is much more difficult. As a result of these challenges, cultural ecosystem services are often the set of services left to last or simply ignored.

Cultural ecosystem services have long since been acknowledged a within Landscape Character Assessments (LCAs), with sense of place, recreational value, historic features and aesthetic quality all being widely reported on within these reports, which first gained traction in the early 90s.

‘Sense of place’ is a key cultural ecosystem service which challenges the ecosystem services approach. This is because sense of place is not only derived from natural capital; drystone walls, street art, stately homes, cultural literary associations such as Wordsworth in the Lakes and brutalist architecture all contribute to sense of place but are clearly not ‘natural capital’. Places are experienced holistically, not as bundles of cultural and natural components.

From both a cultural and ecological perspective, there is a glitch in the assessment of sense of place as a cultural ecosystem service. From an ecological perspective, it means that an area without functioning ecosystems, but strong cultural heritage could potentially receive a score even in the absence of natural capital. Currently, narrowly defined ecosystem service approaches overlook cultural assets within the environment despite them being a vital component of sense of place.

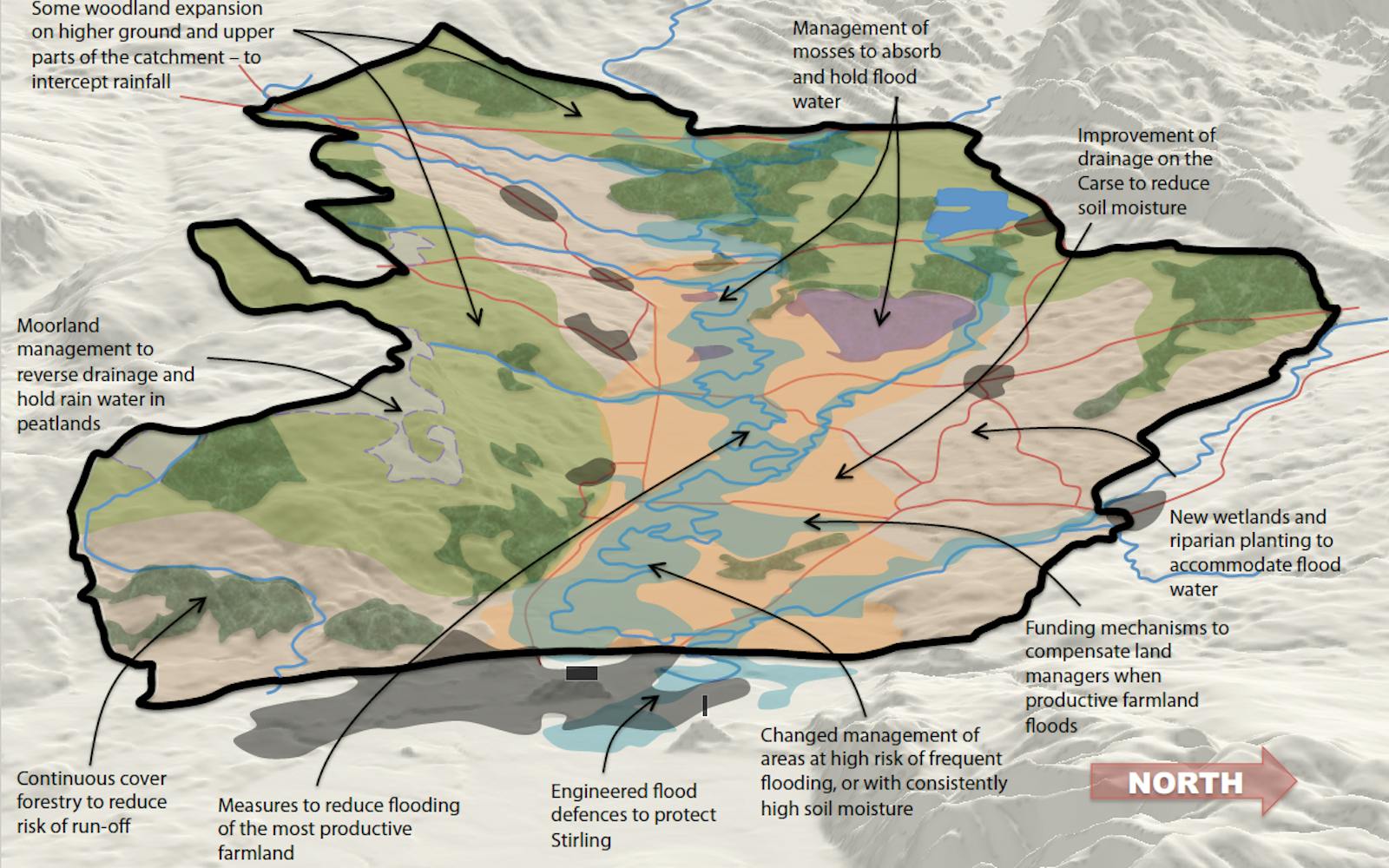

In our work on ecosystem services, we have explored and assessed cultural ecosystem services in detail. We have achieved this through projects such as the award winning Carse of Stirling Ecosystems Approach Demonstration Project and the assessment of cultural ecosystem services delivered by Scotland’s water environment.

Strengthening natural capital and ecosystem services through a place-based approach

At LUC, we are applying our experience at the forefront of Landscape Character Assessment to upcoming natural capital and ecosystem services assessments. This has included developing an ecosystem services element for the national character area profiles which will be further evolved in future. Landscape character provides a spatial framework encompassing both natural and cultural assets.

To further this, in our current natural capital methodologies, we have chosen to map cultural assets as well as natural assets. Although these are obviously not the focus of the assessment, to accurately assess sethe nse of place we need to not only understand how natural assets contribute to it, but how they are elevated by being experienced in conjunction with cultural asses.

We look forward to our continued use of a ‘landscape lens’ to further evolve and refine natural capital and ecosystem service approaches. Landscape is the vessel through which services and benefits are delivered to people.

We aim to create nature-rich areas offering a wide range of benefits and services that respect their locality, identity, sense of place and character, while also recognising the challenges and opportunities of creating new character and new landscape identity